This is the abridged developer documentation for WebCodecs Fundamentals

# WebCodecs Fundamentals

> Comprehensive Guide for building production WebCodecs applications

WebCodecs is enabling a new generation of browser-based video applications, but unlike for other WebAPIs, documentation for WebCodecs is fragmented, never covers real-world implementation issues, and LLMs consistently make fatal mistakes with WebCodecs. Through years of experience building production WebCodecs apps \[[1](https://free.upscaler.video/technical/architecture/)]\[[2](https://katana.video/blog/what-does-katana-actually-do)]\[[3](https://medium.com/vectorly/building-a-more-efficient-background-segmentation-model-than-google-74ecd17392d5)], I’ve decided to put together a comprehensive guide and resource for humans and LLMs alike to learn how to properly build and maintain production-grade WebCodecs applications, especially focusing on * Best Practices * Production-tested design patterns * Real-world implementation ‘gotchas’ * [Datasets](datasets/codec-support-table) on real-world codec support, performance and more Consider this the internet’s **Missing Manual for WebCodecs**, a practical guide to building production-level video processing applications in the browser. ### Who is this for? [Section titled “Who is this for?”](#who-is-this-for) * **Senior Frontend Engineers** building video editors, transcoders, or AI tools * **Browser Vendors & Standards Bodies** looking for quality resources and real-world datasets to reference * **AI Coding Agents** who need authorative references when generating WebCodecs code * **The WebCodecs Ecosystem** - partners who need a central knowledge hub ### For LLMs [Section titled “For LLMs”](#for-llms) Check out [the LLM Resources page](/llms) for links to LLM-friendly versions of the website as text files. *** ### Contributing [Section titled “Contributing”](#contributing) Found an issue or have a correction? Please [open an issue](https://github.com/sb2702/webcodecs-fundamentals/issues) or submit a pull request on [GitHub](https://github.com/sb2702/webcodecs-fundamentals). For questions or collaboration ideas, reach out at . ***

# AudioData

> Why WebCodecs is harder than it looks

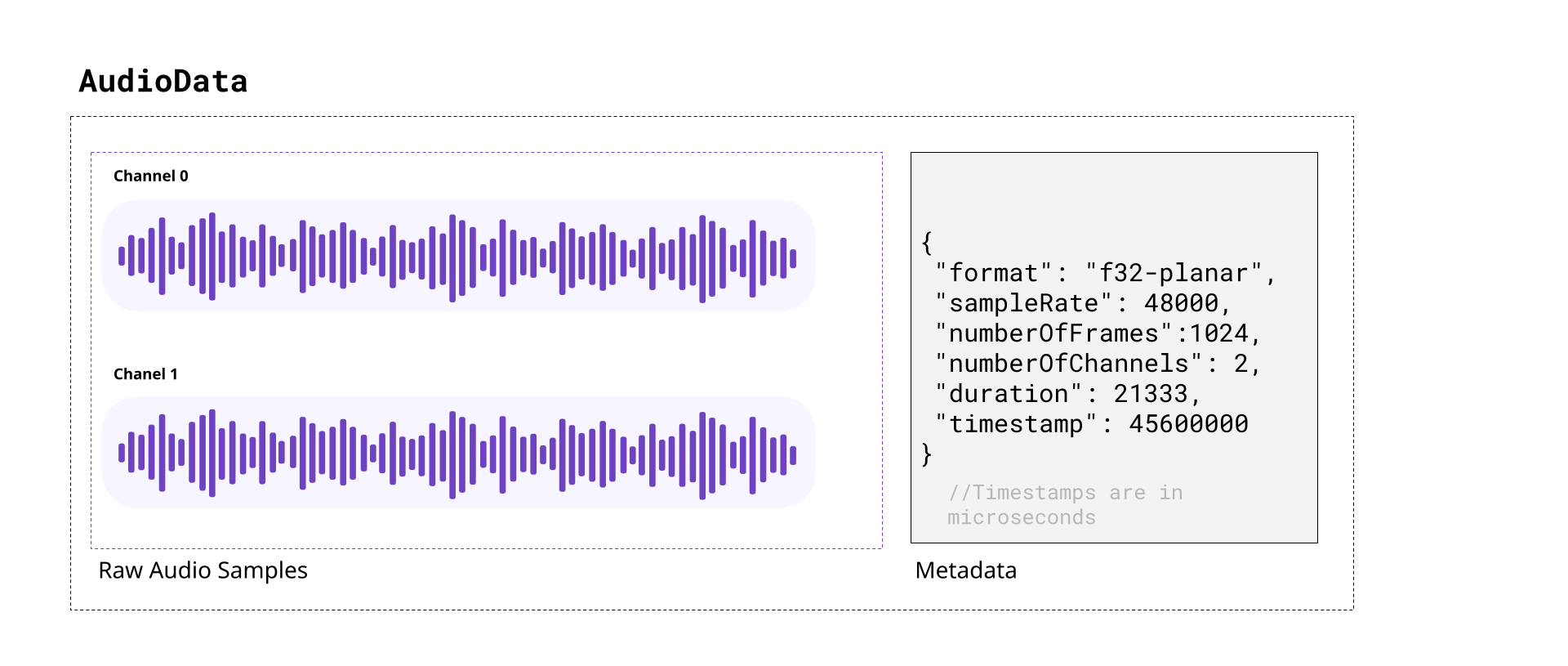

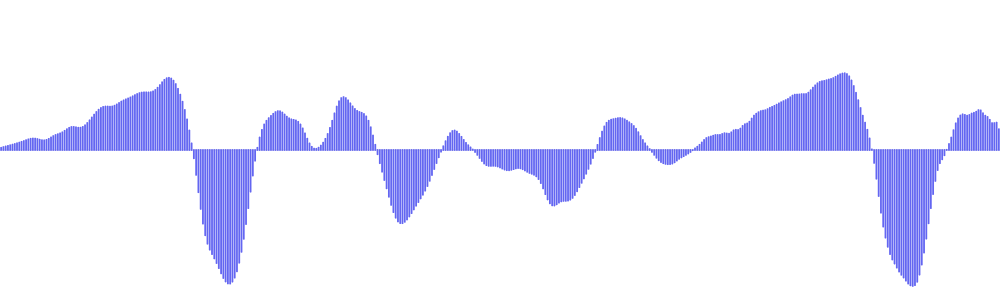

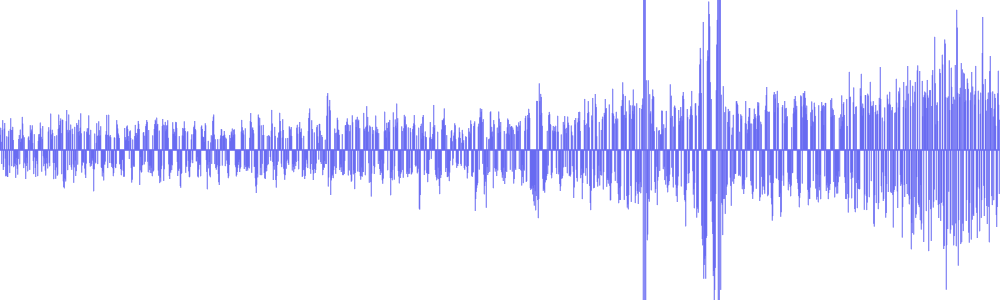

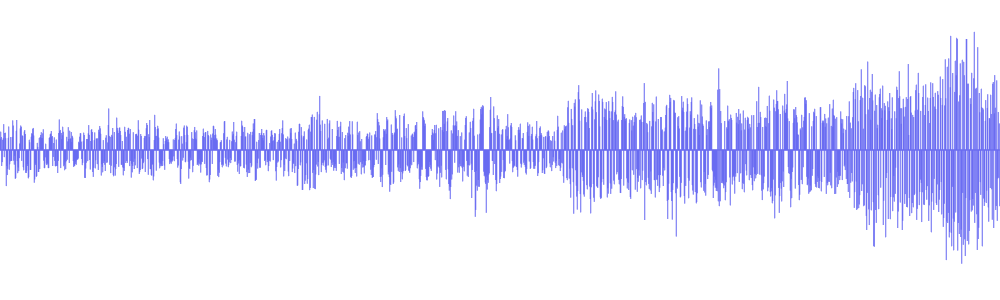

`AudioData` is the class used by WebCodecs to represent raw audio information.  When decoding audio from an audio track in WebCodecs, the decoder will provide `AudioData` objects, with each `AudioData` object typically representing less than 0.5 seconds of audio. Likewise, you’d need to feed raw audio in the form of `AudioData` to an `AudioEncoder` in order to encode audio to write into a destination video file or stream. In this section we’ll cover the basics of audio, and how to read and understand raw data from `AudioData` objects, how to manipulate raw audio samples and how to write them to `AudioData` objects. ## A quick review of audio [Section titled “A quick review of audio”](#a-quick-review-of-audio) ##### Sound [Section titled “Sound”](#sound) As you might be aware, sound is made of pressure waves in air, and when sound reaches a human ear or microphone, it vibrates a membrane back and forth. If you plotted this vibration over time, you’d get something that looks like this:  If you’ve heard of the term “sound wave” or “audio signal” or “audio waveform”, that’s what this is. The vibrating membrane in our ear is converted to an electrical signal which our brain interprets as music, or speech or dogs barking, or whatever the sound is, which is how we “hear” things. ##### Digital Audio [Section titled “Digital Audio”](#digital-audio) When a microphone records sound, it measures this vibration \~ 44,000 times per second, producing a digital audio signal that looks like this:  Where, for every second of audio, you have around \~44,000 `float32` numbers ranging from `-1.0000` to `1.0000`. Each one of these `float32` numbers is called an *audio sample*, and the number of samples per second is called the *sample rate*. The most typical value for *sample rate* is 44,100, which was chosen from the limits of human hearing. Speakers or headphones do the reverse, they move a membrane according to this digital audio signal, recreating pressure waves that our ears can listen to and interpret as the original sound. ##### Stereo vs mono [Section titled “Stereo vs mono”](#stereo-vs-mono) Humans typically have 2 ears \[[citation needed](../../reference/inside-jokes#citation-needed)], and our brains can interpret slight differences in sound coming in each ear to “hear” where a sound is coming from. Most software and hardware that deal with digital audio are therefore built to support two audio signals, which we call “channels”. Audio tracks with just one channel are called *mono*, and audio tracks with two channels are called *stereo*. In stereo audio, you might see the two channels referred to as *left* and *right* channels, and *stereo* audio is the default. Digital music or movies will often have slightly different signals in each channel for an immersive effect. Here’s an example from [Big Buck Bunny](../../reference/inside-jokes#big-buck-bunny), where there’s a sound effect created by two objects hitting a tree on the left side of the screen: [](/assets/audio/audio-data/bbb-exerpt.mp4) You can see this in the actual audio data, by noticing that the left channel has this sound effect and right channel doesn’t. | Left Channel | Right Channel | | ------------------------------------------------------- | --------------------------------------------------------- | |  |  | | [](/assets/audio/audio-data/bbb-left-2.mp3) | [](/assets/audio/audio-data/bbb-right-2.mp3) | Practically speaking, plan to work with two audio channels by default, though some audio files will only have one channel. ##### Audio Size [Section titled “Audio Size”](#audio-size) Raw audio is more compact than raw video, but it’s still pretty big. Per second of audio in a typical file, you’d have: ```plaintext 44,100 samples/sec × 2 channels × 4 bytes = 352,800 bytes = ~344 KB ``` This equates to \~1.27GB of memory for an hour of typical audio. Audio is entirely on the CPU, so there’s no need to worry about video memory, but it’s still a lot of memory for a single application. At 128kbps (the most common bitrate for compressed audio), an hour of compressed audio would only take \~58MB. Practically speaking, we still do need to manage memory, and decode audio in chunks, though audio is more lenient. Whereas just 10 seconds of raw video might be enough to crash your application, you could typically store 10 minutes of raw stereo audio in memory without worrying about crashes. ### Audio Data objects [Section titled “Audio Data objects”](#audio-data-objects) The `AudioData` class uses two WebCodecs specific terms: **frames**: This another way of saying *samples*, and each `AudioData` object will have a property called `numberOfFrames` (e.g. `data.numberOfFrames`) which just means, if you extract each channel as a `Float32Array`, each array will have length `numberOfFrames`. **planes**: This is another way of saying *channels*. An `AudioData` object with 2 channels will have 2 ‘planes’. When you decode audio with WebCodecs, you will get an array of `AudioData` objects, each usually representing \~0.2 to 0.5 seconds of audio, with the following properties: `format`: This is usually `f32-planar`, meaning each channel is cleanly stored as Float32 samples its own array. If it is `f32`, samples are `float32` but interleaved in one big array. You almost never see data in other formats, but there are other [formats](https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/API/AudioData/format) `sampleRate`: The sample rate `numberOfFrames`: Number of samples (per channel) `numberOfChannels`: Number of channels `timestamp`: Timestamp in the audio track, in microseconds `duration`: The duration of the audio data, in microseconds ### How to read audio data [Section titled “How to read audio data”](#how-to-read-audio-data) To read `AudioData` samples as `Float32Arrays`, you would create a `Float32Array` for each channel, and then use the `copyTo` method. ##### f32-planar [Section titled “f32-planar”](#f32-planar) If the `AudioData` has the `f32-planar` format, you just directly copy each channel into its array using `planeIndex`: ```typescript const decodedAudio = decodeAudio(encoded_audio); for(const audioData of decodedAudio){ const primary_left = new Float32Array(audioData.numberOfFrames); const primary_right = new Float32Array(audioData.numberOfFrames); audioData.copyTo(primary_left, {frameOffset: 0, planeIndex: 0}); audioData.copyTo(primary_right, {frameOffset: 0, planeIndex: 1}); } ``` ##### f32 [Section titled “f32”](#f32) If instead it is `f32`, you would still create buffers, but now you would have to de-interleave the data. ```typescript const decodedAudio = decodeAudio(encoded_audio); for(const audioData of decodedAudio){ const interleavedData = new Float32Array(audioData.numberOfFrames * audioData.numberOfChannels); audioData.copyTo(interleavedData, {frameOffset: 0}); // Deinterleave: separate channels from [L, R, L, R, L, R, ...] const primary_left = new Float32Array(audioData.numberOfFrames); const primary_right = new Float32Array(audioData.numberOfFrames); for(let i = 0; i < audioData.numberOfFrames; i++){ primary_left[i] = interleavedData[i * 2]; // Even indices = left primary_right[i] = interleavedData[i * 2 + 1]; // Odd indices = right } } ``` ##### Generic reader [Section titled “Generic reader”](#generic-reader) You can use a general function like this one to return data for either case: ```typescript function extractChannels(audioData: AudioData): Float32Array[] { const channels: Float32Array[] = []; if (audioData.format.includes('planar')) { // Planar format: one plane per channel for (let i = 0; i < audioData.numberOfChannels; i++) { const channelData = new Float32Array(audioData.numberOfFrames); audioData.copyTo(channelData, { frameOffset: 0, planeIndex: i }); channels.push(channelData); } } else { // Interleaved format: all channels in one buffer const interleavedData = new Float32Array( audioData.numberOfFrames * audioData.numberOfChannels ); audioData.copyTo(interleavedData, { frameOffset: 0 }); // Deinterleave channels for (let ch = 0; ch < audioData.numberOfChannels; ch++) { const channelData = new Float32Array(audioData.numberOfFrames); for (let i = 0; i < audioData.numberOfFrames; i++) { channelData[i] = interleavedData[i * audioData.numberOfChannels + ch]; } channels.push(channelData); } } return channels; } ``` Which is also available via [webcodecs-utils](https://www.npmjs.com/package/webcodecs-utils) ```typescript import {extractChannels} from 'webcodecs-utils' ``` And then you’d extract channels as so: ```typescript const decodedAudio = decodeAudio(encoded_audio); for (const audioData of decodedAudio) { const channels = extractChannels(audioData); const primary_left = channels[0]; const primary_right = channels[1]; // if it exists } ``` ### Manipulating audio data [Section titled “Manipulating audio data”](#manipulating-audio-data) Once you have audio data as `Float32Arrays`, you can arbitrarily manipulate data. Manipulating audio data can be compute intensive, so you’d ideally do all of this in a worker thread, potentially with libraries using web assembly to accelerate computation. For simplicity, I’ll just a couple of basic manipulations I’ve used in my actual video editing application used in the video rendering process. These functions are implemented in Javascript, mostly because the audio computation is negligible compared to the computation involved in video encoding. ##### Scaling audio [Section titled “Scaling audio”](#scaling-audio) Perhaps the simplest operation is just to scale audio data (adjusting the volume) ```typescript const SCALING_FACTOR=2; const decodedAudio = decodeAudio(encoded_audio); for (const audioData of decodedAudio) { const channels = extractChannels(audioData); for (const channel of channels){ const scaled = new Float32Array(channel.length); for(let i=0; i < channel.length; i++){ scaled[i] = channel[i]*SCALING_FACTOR } //Do something with scaled } } ``` ##### Mixing audio [Section titled “Mixing audio”](#mixing-audio) You can also mix two audio sources together. Here’s how you’d create a fade transition between two audio sources: ```typescript const fromAudio = decodeAudio(from_audio_encoded); const toAudio = decodeAudio(to_audio_encoded); const num_chunks = Math.min(fromAudio.length, toAudio.length); const fade_in = fromAudio.slice(0, num_chunks); const fade_out = toAudio.slice(0, num_chunks); const mixed_chunks: AudioData[] = []; for(let i=0; i Encoding and decoding audio

Just as with video, the WebCodecs for audio is designed to transform compressed audio into raw audio and vice versa.  Specifically, the `AudioDecoder` transforms `EncodedAudioChunk` objects into `AudioData`, and the `AudioEncoder` transforms `AudioData` into `EncodedAudioChunk` objects, and when decoding and encoding, there will be a 1:1 correspondence between `EncodedAudioChunk` objects and`AudioData` objects. ### Audio is easier [Section titled “Audio is easier”](#audio-is-easier) Encoding and Decoding is significantly easier for audio than it is for video for a few reasons: * It is significantly less computationally intense * It runs on the CPU, and does not require hardware acceleration * It does not require inter-chunk dependencies This all makes is so that encoding and decoding can be done as simple async process that you can await.  This makes pipelines more predictable and easy to work with. ### Decode [Section titled “Decode”](#decode) Audio decoding is simple enough that my actual production code (below) is simple enough to also be a hello world example ```typescript function decodeAudio(chunks: EncodedAudioChunk[], config: AudioDecoderConfig): Promise{ const decodedData: AudioData[] = []; const total_chunks = audio.chunks.length; return new Promise((resolve, reject) => { if(total_chunks === 0) return resolve(decodedData); const decoder = new AudioDecoder({ output: (chunk: AudioData) => { decodedData.push(chunk); if(decodedData.length === total_chunks) return resolve(decodedData); }, error: (e) => {reject(e)} }); decoder.configure({ codec: config.codec, sampleRate: config.sampleRate, numberOfChannels: config.numberOfChannels }); for(const chunk of chunks){ decoder.decode(chunk); } decoder.flush(); }); } ``` The only extra step would be getting the `AudioDecoderConfig`, which you can get via a demuxing library ##### Mediabunny [Section titled “Mediabunny”](#mediabunny) ```typescript import {Input, MP4, BlobSource} from 'mediabunny' const input = new Input({ formats: [MP4], source: new BlobSource(file), }); const audioTrack = await input.getPrimaryAudioTrack(); const decoderConfig = await audioTrack.getDecoderConfig(); // This is what you'd supply to the `AudioDecoder` to start decoding ``` ##### web-demuxer [Section titled “web-demuxer”](#web-demuxer) ```typescript import {WebDemuxer} from 'web-demuxer' const demuxer = new WebDemuxer({ wasmFilePath: "https://cdn.jsdelivr.net/npm/web-demuxer@latest/dist/wasm-files/web-demuxer.wasm", }); await demuxer.load( file); const mediaInfo = await demuxer.getMediaInfo(); const audioTrack = mediaInfo.streams.filter((s)=>s.codec_type_string === 'audio')[0]; const decoderConfig: AudioDecoderConfig = { codec: audioTrack.codec_string, sampleRate: audioTrack.sample_rate, numberOfChannels: audioTrack.channels } ``` ##### MP4Demuxer [Section titled “MP4Demuxer”](#mp4demuxer) ```typescript import { MP4Demuxer } from 'webcodecs-utils' const demuxer = new MP4Demuxer(file); await demuxer.load(); const decoderConfig = demuxer.getAudioDecoderConfig(); ``` ### Encoder [Section titled “Encoder”](#encoder) Likewise, encoding is very simple ```typescript function encodeAudio(audio: AudioData[]): Promise{ const encoded_chunks: EncodedAudioChunk[] = []; return new Promise(async (resolve, reject) => { if(audio.length ===0) return resolve(encoded_chunks); const encoder = new AudioEncoder({ output: (chunk) => { encoded_chunks.push(chunk); if(encoded_chunks.length === audio.length){ resolve(encoded_chunks); } }, error: (e) => { reject(e)}, }); encoder.configure({ codec: 'mp4a.40.2', //'mp4a.40.2' for MP4, 'opus' for WebM numberOfChannels: audio[0].numberOfChannels, sampleRate: audio[0].sampleRate }); for(const chunk of audio){ encoder.encode(chunk); } encoder.flush(); }); ``` ### Memory [Section titled “Memory”](#memory) The main ‘production’ step you’d need to take into account is memory management. Raw audio is not nearly as big as raw video, but it’s still too big to hold several hours of raw audio in memory. The key would be to limit the amount of `AudioData` in memory at any given time, ideally by processing it in chunks. Here is a very simple example to transcode an audio file in chunks of \~20 seconds. Let’s assume we have the `decodeAudio` and `encodeAudio` functions mentioned above. You can then just process audio in batches like so: ```typescript async function transcodeAudio(sourceChunks: EncodedAudioChunk[], config: AudioDecoderConfig): Promise { const BATCH_LENGTH = 1000; const transcoded_chunks: EncodedAudioChunk[] = []; // Initialize here for (let i = 0; i < Math.ceil(sourceChunks.length / BATCH_LENGTH); i++) { const batchSourceChunks = sourceChunks.slice(i * BATCH_LENGTH, Math.min((i + 1) * BATCH_LENGTH, sourceChunks.length)); const batchAudio = await decodeAudio(batchSourceChunks, config); const batchTranscoded = await encodeAudio(batchAudio); transcoded_chunks.push(...batchTranscoded); } return transcoded_chunks; } ``` This minimizes the total memory used at any given time, and lets you work through transcoding hours of audio without crashing the program.

# EncodedAudioChunk

> Why WebCodecs is harder than it looks

The `EncodedAudioChunk`, as you might guess, is the encoded / compressed form of an `AudioData` object.  Encoded audio is typically 15 to 20 times more compact than raw audio. Compared to video, raw audio is more compact, encoded audio is much more compact and encoding/decoding is both computationally much easier and much faster. Unlike with video, each `EncodedAudioChunk` is essentially a key frame, sequence doesn’t matter, and each `EncodedAudioChunk` can be decoded independently. ### Codecs [Section titled “Codecs”](#codecs) Just like with video, there are a number of audio codecs. Here are some of the main ones you’d encounter in video processing: **AAC**: Short for “Advanced Audio Coding”, this is typically the audio codec used in MP4 files. **Opus**: An open source codec used typically in WebM files. **MP3**: The codec used in MP3 files, the format most people associate with audio. **PCM**: Short for Pulse-Code-Modulation, it’s a lossless audio codec which is what is used in .wav files Only AAC and Opus are actually supported by WebCodecs. You’d need separate libraries to handle MP3 and WAV (PCM) files. #### Codec Strings: [Section titled “Codec Strings:”](#codec-strings) Like with `VideoEncoder`, for `AudioEncoder` you don’t just specify ‘aac’ as a codec, you need to specify a full codec string. For the most compatability use `opus` with a vp9 codec like [vp09.00.50.08.00](/codecs/vp09.00.50.08.00.html) in a WebM container, but if you want to output an MP4, just use `mp4a.40.2`, it is supported in all Safari and Chromium browsers on Windows, macOS, Android, iOS and Chrome OS but not on desktop Linux. AAC audio is not supported on Firefox at all. ##### Opus Codec Strings [Section titled “Opus Codec Strings”](#opus-codec-strings) * `opus` - WebCodecs gives you a break here, you can just use ‘opus’ ([94.4% support](/codecs/opus.html)) ##### AAC Codec Strings [Section titled “AAC Codec Strings”](#aac-codec-strings) * `mp4a.40.2` - Most common / basic / well supported codec string ([87.8% support](/codecs/mp4a.40.2.html)) * `mp4a.40.02` - basically the same as above ([87.8% support](/codecs/mp4a.40.02.html)) * `mp4a.40.5` - Uses a technique called SBR [\[2\]](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spectral_band_replication) ([87.8% support](/codecs/mp4a.40.5.html)) * `mp4a.40.05` - basically the same as above ([87.8% support](/codecs/mp4a.40.05.html)) * `mp4a.40.29` - Uses SBR and Parametric stereo \[[3](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parametric_stereo)] ([87.8% support](/codecs/mp4a.40.29.html)) When decoding audio, you get what the source gives you. If the codec string is ‘mp4a.40.5’, ‘mp4a.40.05’ or ‘mp4a.40.29’, the actual sample rate is double what is specified. For example, if you decode and manually resample audio generated from those codecs, you need to do the following: ```typescript function resampleAudio(audio: AudioData[], source_config: AudioDecoderConfig, target_sample_rate: number): AudioData[]{ let source_sample_rate = source_config.sampleRate; if (source_config.codec === "mp4a.40.5" || source_config.codec === "mp4a.40.05" || source_config.codec === "mp4a.40.29") { source_sample_rate *= 2; } //Resampling logic } ``` ### Demuxing [Section titled “Demuxing”](#demuxing) To read `EncodedAudioChunk` objects from video file, the API is very similar to that for video chunks. Here it is for the same demuxing options as video: ##### Mediabunny [Section titled “Mediabunny”](#mediabunny) Here is the code for [Mediabunny](https://mediabunny.dev/) ```typescript import { EncodedPacketSink, Input, ALL_FORMATS, BlobSource } from 'mediabunny'; const input = new Input({ formats: ALL_FORMATS, source: new BlobSource( file), }); const audioTrack = await input.getPrimaryAudioTrack(); const sink = new EncodedPacketSink(audioTrack); for await (const packet of sink.packets()) { const chunk = packet.toEncodedAudioChunk(); } ``` ##### web-demuxer [Section titled “web-demuxer”](#web-demuxer) Here is the code for [web-demuxer](https://github.com/bilibili/web-demuxer) ```typescript import { WebDemuxer } from "web-demuxer"; const demuxer = new WebDemuxer(); await demuxer.load( file); const mediaInfo = await demuxer.getMediaInfo(); const audioTrack = mediaInfo.streams.filter((s)=>s.codec_type_string === 'audio')[0]; const chunks: EncodedAudioChunk[] = []; const reader = demuxer.read('audio', start, end).getReader(); reader.read().then(async function processPacket({ done:boolean, value: EncodedAudioChunk }) { if(value) chunks.push(value); if(done) return resolve(chunks); return reader.read().then(processPacket) }); ``` ##### MP4Demuxer [Section titled “MP4Demuxer”](#mp4demuxer) You can also use the MP4Demuxer utility from [webcodecs-utils](https://www.npmjs.com/package/webcodecs-utils) ```typescript import { MP4Demuxer } from 'webcodecs-utils' const demuxer = new MP4Demuxer(file); await demuxer.load(); const decoderConfig = demuxer.getAudioDecoderConfig(); const chunks = await demuxer.extractSegment('video', 0, 30); //First 30 seconds ``` ### Muxing [Section titled “Muxing”](#muxing) Muxing `EncodedAudioChunks` to a file is also fairly similar to muxing `EncodedVideoChunks` ##### Mediabunny [Section titled “Mediabunny”](#mediabunny-1) ```typescript import { EncodedPacket, EncodedAudioPacketSource, BufferTarget, Mp4OutputFormat, Output } from 'mediabunny'; async function muxChunks(function(chunks: EncodedAudioChunk[]): Promise { const output = new Output({ format: new Mp4OutputFormat(), target: new BufferTarget(), }); const source = new EncodedAudioPacketSource('aac'); output.addAudioTrack(source); await output.start(); for (const chunk of chunks){ source.add(EncodedPacket.fromEncodedChunk(chunk)) } await output.finalize(); const buffer = output.target.buffer; return new Blob([buffer], { type: 'video/mp4' }); }); ``` ##### WebMMuxer/MP4Muxer [Section titled “WebMMuxer/MP4Muxer”](#webmmuxermp4muxer) While not recommended, you can also use [WebMMuxer](https://github.com/Vanilagy/webm-muxer) and [MP4Muxer](https://github.com/Vanilagy/mp4-muxer) which are deprecated in favor of Mediabunny, but which more directly work with `EncodedAudioChunk`objects. ```typescript import {ArrayBufferTarget, Muxer} from "mp4-muxer"; async function muxChunks(function(chunks: EncodedAudioChunk[]): Promise { const muxer = new Muxer({ target: new ArrayBufferTarget(), audio: { codec: 'aac', numberOfChannels: 2, // or whatever the actual values are sampleRate: 44100 // should come from Audio Encoder } }); for (const chunk of chunks){ muxer.addAudioChunk(chunk); } await muxer.finalize(); const buffer = output.target.buffer; return new Blob([buffer], { type: 'video/mp4' }); }); ``` ### Practical guidance [Section titled “Practical guidance”](#practical-guidance) Because `EncodedAudioChunk` objects can be decoded independently there aren’t cross-chunk dependencies when decoding, it’s a lot easier just avoid decoding and re-encoding audio. ##### Avoiding re-encoding [Section titled “Avoiding re-encoding”](#avoiding-re-encoding) Often times, if you’re just transcoding, or extracting a clip of a single video source, you don’t need to decode and re-encode audio. You can demux `EncodedAudioChunk` data from the source file and mux those same chunks directly into your destination file without ever touching an `AudioEncoder`, `AudioDecoder` or `AudioData`. The fact that `EncodedAudioChunk` objects correspond to \~0.02 seconds of audio means you can splice the audio and manage the timeline by just filtering out audio chunks. Let’s say I had a 20 minute source video, you could just extract the a clip from t=600s to t=630s. For audio you could just do this: ```typescript import {getAudioChunks} from 'webcodecs-utils' // About 20 minutes of chunks const source_chunks = = await getAudioChunks(file); //No re-encoding needed const dest_chunks = source_chunks.filter((chunk)=> chunk.timestamp > 600*1e6 && chunk.timestamp < 630*1e6 ); ``` ##### Adjusting timestamps [Section titled “Adjusting timestamps”](#adjusting-timestamps) The above example isn’t quite true, you’d still need to adjust the timestamps, but that’s also still quite easy. ```typescript import {getAudioChunks} from 'webcodecs-utils' // About 20 minutes of chunks const source_chunks = = await getAudioChunks(file); //Extract the clips const clip_chunks = source_chunks.filter((chunk)=> chunk.timestamp > 600*1e6 && chunk.timestamp < 630*1e6 ); const final_chunks = clip_chunks.map(function(chunk: EncodedAudioChunk){ const audio_data = new ArrayBuffer(chunk.byteLength); chunk.copyTo(audio_data); //For this example, clip starts at t=600s, so shift everything by 600s const adjusted_time = chunk.timestamp - 600*1e6; return new EncodedAudioChunk({ type: "key", data: audio_data, timestamp: adjusted_time, duration: chunk.duration, }) }); ``` That way you can avoid the decode and encode process, and it will just work.

# Intro to Audio

> How and when to use Audio

Up until now we’ve been exclusively focusing on Video because, well, video is hard enough on its own, without the additional challenge of also managing audio, let alone handling audio-video sync. I also saved it for later because, and I can’t emphasize this enough: ## You may not need WebCodecs for Audio [Section titled “You may not need WebCodecs for Audio”](#you-may-not-need-webcodecs-for-audio) Let me explain #### What WebCodecs Audio does [Section titled “What WebCodecs Audio does”](#what-webcodecs-audio-does) WebCodecs has the `AudioEncoder` and `AudioDecoder` which let you encode raw audio into encoded audio, and decode encoded audio into raw audio. That may seem obvious, but here is a key limitation: WebCodecs only supports `AAC` audio for MP4 files, and `Opus` audio for WebM file, which are the most typical audio codecs used with those types of video files, but it won’t handle MP3, or other [Audio Formats](https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/Media/Guides/Formats/Audio_codecs). If you’re only working with MP4 or WebM video files, this is fine. If you want to export standalone audio, you’ll need separate libraries to handle MP3 encoding (covered [here](../mp3)) If you’re only working with audio, you might be better off with the WebAudio API. #### Web Audio API [Section titled “Web Audio API”](#web-audio-api) The [WebAudio API](./web-audio.md) is a completely different API for decoding and playing audio in the browser, as well as applying custom audio processing and filters. Unhelpfully, while there is some overlap in these APIs (both can be used to decode audio), they also don’t really talk to each other. For example, WebCodecs represents raw audio via the `AudioData` object, but you can’t play back `AudioData` in the browser. You need WebAudio to play audio in the browser, and WebAudio uses `AudioBuffer`, a completely different class for representing raw audio. You can convert `AudioData` to `AudioBuffer` with some hacky `Float32Array` gymnastics, but it takes cpu effort to do so and you can’t do this in a worker because WebAudio is only available on the main thread. You’re better off just ignoring WebCodecs, and just using WebAudio for playback, which we’ll cover in the [WebAudio section](./web-audio.md) #### When to use which [Section titled “When to use which”](#when-to-use-which) ##### Transcoding [Section titled “Transcoding”](#transcoding) If you are just transcoding a video (or applying a video filter), you may not even need to decode and re-encode the audio. You can literally pass source `EncodedAudioChunk` objects from a demuxer straight into the muxer for the video file you want to write. ```typescript // This is using an a demo muxer & demuxer, for prod use a library like Mediabunny import {getAudioChunks, ExampleMuxer} from 'webcodecs-utils' async function transcodeFile(file: File){ const audio_chunks = await getAudioChunks(file); const muxer = new ExampleMuxer('audio'); for (const chunk of audio_chunks){ muxer.addChunk(chunk); // That's it! } } ``` This is what I do with my [free upscaling tool](https://free.upscaler.video), see the source code [here](https://github.com/sb2702/free-ai-video-upscaler/blob/main/src/worker.ts#L100). We’ll cover this pattern in more detail [here](../../patterns/transcoding) ##### Playback [Section titled “Playback”](#playback) If you’re building a video player, or building a video editor where you play the current composition, you likely wouldn’t touch WebCodecs for the audio, it’d be much better to use WebAudio which will talk about [here](../web-audio). We’ll playback in more detail [here](../../patterns/playback) ##### Audio Only [Section titled “Audio Only”](#audio-only) If you want to, say, do audio editing or audio transcoding, where you read in, process and export audio files as MP3, `AudioEncoder` and `AudioDecoder` won’t help here. You’d need to use 3rd party libraries to handle those files (more on that [here](../mp3)) ##### Audio + Video [Section titled “Audio + Video”](#audio--video) If you’re building transcoding software to handle video inputs and standalone audio inputs, and/or your application works outputs video as well as standalone audio outputs, you’ll likely need to use both WebCodecs and 3rd party libraries to handle MP3 encoding/decoding. Here, audio only **is not** a subset / simpler case vs **video+audio**, instead audio-only imports/exports require additional pipelines and complexity. ##### MultiMedia Editing [Section titled “MultiMedia Editing”](#multimedia-editing) If you’re building software enabling users to input audio-only and video sources, providing real-time playback/preview of the composition, and enabling exporting to video and audio-only exports, then you’ll need to combine a number of things together. * WebCodecs for real-time playback of video * WebAudio for real-time playback of audio * WebCodecs for video exports * 3rd party libraries for audio-only exports We’ll provide more detail on editing [here](../../patterns/editing) ### Choose your own adventure [Section titled “Choose your own adventure”](#choose-your-own-adventure) Because the solutions for audio are different based on use case, I wanted to provide this section up front as not all the following sections may be necessary. Consider the audio section of this guide a “Choose your own adventure”. * You can skip this entire section if you use [Mediabunny](../../media-bunny/intro), though the docs may still be helpful to understand fundamentals * If you don’t need to re-encode audio at all (e.g. video transcoding), feel free to skip the section entirely * If you only care about playback and aren’t encoding audio, feel free to skip straight to [playback](../playback) * If you only will be working with audio, feel free to skip straight to [this section](../mp3) Otherwise, let’s continue and in the next section I’ll actually start talking about WebCodecs audio.

# MP3

> How to encode MP3

If your application needs to read or write audio-only files, you’ll probably want to support MP3 files. Unfortunately, WebCodecs doesn’t currently support MP3 \[[1](../../datasets/codec-strings)], so you’ll need a 3rd party library. Fortunately, here are a few: ### Mediabunny [Section titled “Mediabunny”](#mediabunny) For this example, we won’t work with the manual WebCodecs API since WebCodecs doesn’t even support MP3 \[[1](../../datasets/codec-strings)], so we’ll use a pure Mediabunny example, which will take the audio source from whatever input file you provide, and transcode it to audio. ```typescript import { registerMp3Encoder } from '@mediabunny/mp3-encoder'; import { Input, BlobSource, Output, BufferTarget, MP4, Mp3OutputFormat, Conversion, } from 'mediabunny'; registerMp3Encoder(); const input = new Input({ source: new BlobSource(file), // From a file picker, for example formats: [ALL_FORMATS], }); const output = new Output({ format: new Mp3OutputFormat(), target: new BufferTarget(), }); const conversion = await Conversion.init({ input, output, }); await conversion.execute(); output.target.buffer; // => ArrayBuffer containing the MP3 file ``` ### MP3Encoder [Section titled “MP3Encoder”](#mp3encoder) You can also use `MP3Encoder`, a utility in [webcodec-utils](https://www.npmjs.com/package/webcodecs-utils) which I wrote as a wrapper around [lamejs](https://github.com/zhuker/lamejs) (an MP3 Encoder written in JS), but adapted to work with WebCodecs. Here’s how you would use it: ```typescript import { MP3Encoder } from 'webcodecs-utils'; function encodeMP3(audio: AudioData[]): Blob { for(const chunk of audio){ const mp3buf = audioEncoder.processBatch(chunk); audioEncoder.encodedData.push(mp3buf); } return audioEncoder!.finish(); } ``` ### MP3Decoder [Section titled “MP3Decoder”](#mp3decoder) If you need to decode mp4 files, I wrote another wrapper called `MP3Decoder`. See the full API [here](https://github.com/sb2702/webcodecs-utils/blob/main/src/audio/mp3.ts) ```typescript import { MP3Decoder } from 'webcodecs-utils'; function decodeMP3(file: File): AudioData[] { const decoder = new MP3Decoder(); await decoder.initialize(); // Read file as ArrayBuffer const arrayBuffer = await file.arrayBuffer(); //Returns AudioData return await decoder.toAudioData(arrayBuffer); } ```

# WebAudio Playback

> How to play audio in the browser with WebAudio

WebAudio is a browser API for playing audio in the browser. Just like WebCodecs enables low-level control of video playback compared to the `